In veterinary medicine, the ability to perform a quick and successful canine intravenous (IV) catheterization is a cornerstone of clinical practice. Whether it’s for fluid therapy, medication administration, or emergency resuscitation, mastering this skill is essential for every veterinary student and technician.

This guide serves as a deep dive into the technical, anatomical, and educational aspects of canine IV catheterization.

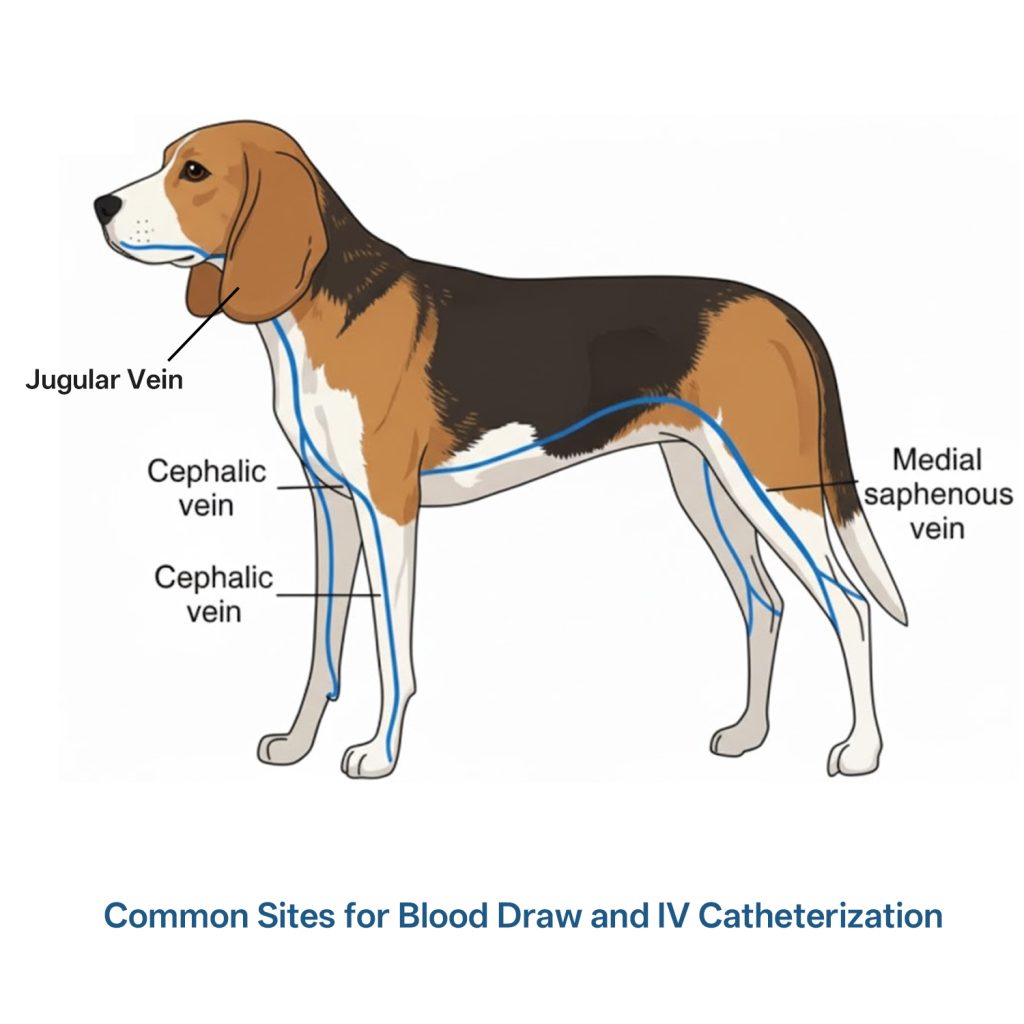

1. Anatomical Foundations: Selecting the Optimal Site

1.1 The Cephalic Vein: The Gold Standard

Located on the cranio-medial aspect of the forelimb, the cephalic vein is the most common site for peripheral access.

- Clinical Advantage: It is relatively superficial and easy to stabilize against the radius.

- Physiological Note: In “rolled” veins, the cephalic can be elusive. Advanced practitioners know that anchoring the vein distally is the secret to preventing the vessel from “rolling” away from the needle tip.

1.2 The Lateral Saphenous Vein: The Strategic Alternative

Found on the lateral aspect of the hindlimb, just proximal to the hock.

- When to use: This site is ideal for patients with head or forelimb trauma, or when the medical team needs to remain at the rear of an aggressive dog.

- The Challenge: This vein is more mobile than the cephalic and requires a very sharp angle of entry and firm skin tension.

1.3 Hemodynamics and Vessel Quality

The “feel” of a vein changes based on the patient’s blood pressure. A hypotensive dog (in shock) will have “flat” veins that lack the turgidity required for easy penetration.

2. Choosing Canine Catheter Sizes

Choosing the correct gauge (diameter) is as vital as the insertion technique itself. The rule of thumb in veterinary medicine is: “Use the largest gauge that can be comfortably and safely placed in the vessel.” A larger gauge allows for faster fluid resuscitation and reduces the risk of catheter occlusion.

2.1 The Gauge Selection Chart

| Patient Size/Type | Recommended Gauge | Common Color Code | Clinical Use Case |

| Large Dogs (>30kg) | 18G | Green | Rapid fluid boluses, emergency trauma, large breed surgery. |

| Medium Dogs (10-30kg) | 20G | Pink | Standard for most adult dogs; ideal for routine IV fluids. |

| Small Dogs (<10kg) / Puppies | 22G | Blue | Pediatric cases or dogs with fragile/small vessels. |

| Toy Breeds / Neonates | 24G | Yellow | Fragile vessels; restricted to slow infusion or blood sampling. |

2.2 Factors Influencing Your Choice

Viscosity of Fluids: If you are administering whole blood or thick colloids, a 20G or larger is required to prevent hemolysis and ensure flow.

Duration of Therapy: For long-term hospitalization, a slightly smaller gauge may cause less irritation to the vessel wall (phlebitis), whereas emergency shock requires the maximum diameter possible.

Vessel Condition: In dehydrated patients, vessels are “flat.” It is often wiser to successfully place a 22G on the first try than to blow the vein attempting to force an 18G.

3. The Step-by-Step Clinical Protocol (SOP)

3.1 Pre-Procedural Preparation

Success is 90% preparation. Beyond your catheter, ensure your tape is pre-cut and your saline flush is primed to avoid “air-lock” complications.

3.2 Stabilization: The Three-Point Anchor

Place your non-dominant thumb parallel to the vein, roughly 1 cm distal to the intended puncture site. Gently pull the skin toward the paw. This creates tension, “pinning” the vein in place.

3.3 The Puncture: Angle and Velocity

- Initial Entry: Enter the skin at a 20 to 30-degree angle.

- The “Pop”: You should feel a distinct decrease in resistance as you puncture the tunica externa of the vein.

- The Flashback: Watch the “flash chamber.” The moment blood appears, you have achieved intraluminal access.

3.4 The Critical “Advance”

This is where most beginners fail. Upon seeing the flashback, do not stop. Decrease your angle to 10 degrees (almost parallel to the limb) and advance the entire unit (needle and cannula) another 2–3 millimeters. This ensures that the blunt plastic cannula tip is also inside the vessel, not just the sharp needle tip.

4. Advanced Troubleshooting: Solving Clinical Failures

A deep guide must address what happens when things go wrong.

4.1 “Flash but No Flow”

You see a flash of blood, but when you try to advance the cannula, it meets resistance.

- The Valve Obstacle: You may be resting against a venous valve.

- Solution: Try “floating” the catheter in by attaching a syringe of saline and gently flushing while you advance.

- The False Flash: The needle may have passed through the vein (transfixion).

- Solution: Slowly withdraw the needle until blood flows again, then advance only the cannula.

4.2 Hematoma Management

If the area begins to swell instantly, you have “blown” the vein.

- The Fix: Remove the catheter immediately and apply firm pressure for at least 3–5 minutes. Never attempt a second stick in the same spot; always move proximal (closer to the body) to the original site.

4.3 Dealing with Thick Skin (The “Labrador” Effect)

Some breeds have incredibly tough, mobile skin. In these cases, a “pre-nick” or “facilitative incision” with a larger gauge needle may be necessary to prevent the catheter tip from fraying or “accordioning” upon entry.

5. Post-Insertion Care and Complication Prevention

A successful stick is only the beginning. Proper maintenance prevents phlebitis and infection.

- Securing the Hub: Use the “Chevron” taping method. It allows for security while leaving the insertion site visible for daily inspection.

- The Saline Flush: Every 4 to 6 hours, the line should be flushed with heparinized saline to prevent clots (thrombi) from forming at the tip.

- Monitoring for Phlebitis: Watch for redness, heat, or “ropiness” of the vein proximal to the catheter. If these occur, the line must be pulled immediately.

6. Useful Tools

Medtacedu provides Canine IV Injection Model Kit for veterinary students to develop “muscle memory” on IV insertion.

Using a Canine IV Catheterization Model allows students to:

Repeat indefinitely: Practice the “feel” of popping through the skin and vein walls without harming an animal.

Learn Flash back Recognition: Visual confirmation is key to student confidence.

Refine Taping Techniques: Mastering the securement process without the distraction of a moving patient.

MEDTACEDU Contraceptive Guidance Model with Suction Cup

MEDTACEDU Contraceptive Guidance Model with Suction Cup